By Natalie Haynes – 22nd January 2018

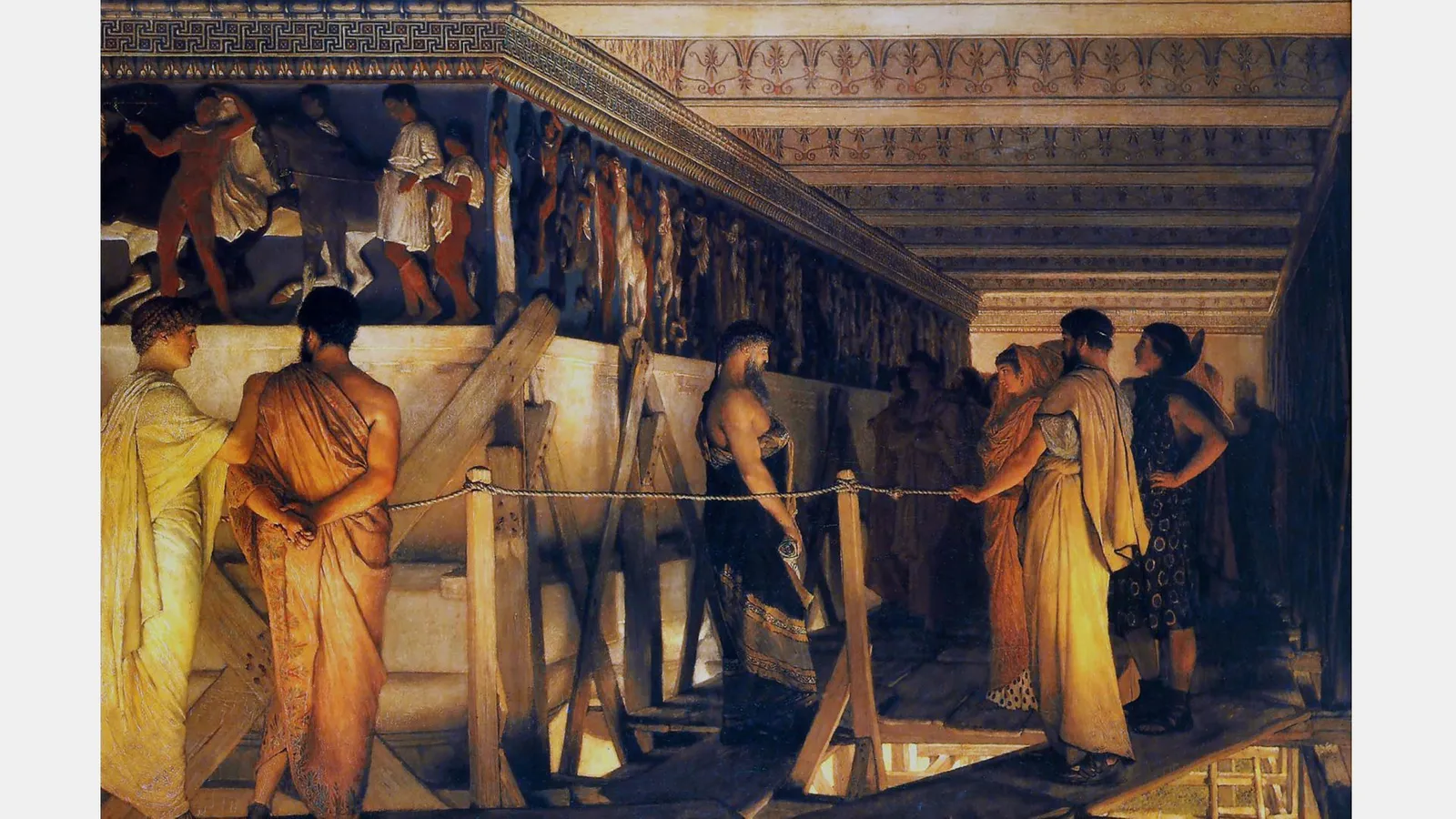

When the Victorian painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema first showed his work, Phidias Showing the Frieze of the Parthenon to his Friends, there must have been a pleasing circularity in play: a painter proudly revealing his new painting of a sculptor proudly revealing his new sculpture. It was 1868, and to the modern viewer the painting looks inoffensive enough. Phidias, the bearded sculptor, stands in front of the Parthenon Frieze, whose characters – human and equine alike – Alma-Tadema would have been able to study in detail in the British Museum. Luminaries of 5th Century Athens admire the sculptor’s extraordinary work: the draperies, the incredible depth (sometimes four horses gallop beside one another in just an inch or two of marble). The viewers might also be remarking upon the dark, beautiful colours that bring the sculpture to life.

Many art historians preferred to imagine, incorrectly, that all ancient marble was gleaming white

Alma-Tadema was making a bold statement with this painting: the colour had been lost from the sculptures by the time they were shown in the British Museum. More than two millennia of weather and war had bleached the marble white. And from the 18th Century onwards, many influential art historians preferred things that way: men like Johann Joachim Winckelmann – whose two-volume history of ancient art was published in 1764 – liked to think of ancient sculpture as a mass of beautiful, gleaming white.

Winckelmann was a particular fan of Roman marble copies of Greek bronze statues: the Romans often copied Greek originals in marble. You can tell it is a marble copy of a bronze if a figure is leaning on something: a tree trunk, or a staff, for example. Or perhaps there is a little chunk of marble joining the two legs together. Marble lacks the tensile strength of bronze, so it requires extra support to keep the figures stable.

So when Alma-Tadema painted the Parthenon Frieze and included his imagined version of the lost colour, he was picking a side in an art history battle which still rages today. There are plenty of people now who find the notion of painted marble or bronze an affront to their impression of the past as an austere, unadorned place.

Yet ancient art would have been a riot of colour and glitzy decoration. Phidias – the most celebrated sculptor of his day – also created a huge statue of Athena Parthenos to stand inside the Parthenon (it takes its name from the description of the goddess: parthenos means ‘maiden’). Although the statue is long since destroyed, we have a description of it in the writings of the ancient historian, Pausanias. He tells us the statue was chryselephantine: covered in gold and ivory. There is a modern-day replica of the statue in Nashville, by the sculptor Alan LeQuire, which surely captures something of the glittering original.

Dulled by time

Even bronze statues would have been much brighter than their dark brown appearance suggests today: bronze acquires a patina over time. What we see as a uniform greenish-brown head would once have been gleaming bright, almost golden. Hair would have been painted dark and the flesh might well have been painted too. The eye sockets of ancient statues are often empty, because the eyes were made separately, and they have been lost over time. There is a magnificent pair of Greek eyes in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, made of bronze, marble, quartz and obsidian. The bronze eyelashes are particularly delightful, if a little disconcerting.

Ultraviolet light can be used to detect traces of colour on otherwise bare statues

Archaeologists have been able to use ultra-violet light to read colour on statues which retain no obviously visible signs of their decoration. Although it is not always possible to identify the precise colours used, the patterns which were painted onto the surface of a statue are often easier to spot. The statues from the Temple of Aphaia on the Greek island of Aigina are a perfect illustration of this. The statues from the western pediment of the temple are now housed in the Glyptothek in Munich, where German archaeologist Vinzenz Brinkmann has examined them under UV light. The pediment had Athena at its centre, her plumed helmet tucking in beneath the highest point of the roof. In UV light, we can finally see the repeating, geometric decoration of her snaking shawl and the front of her robe.

Further along, bending into the lower part of the slanted roof, was the figure of an archer (perhaps Paris, son of Priam of Troy). On his arms and legs, we can see traces of a diamond pattern. Brinkmann has spent years recreating the brightly-coloured decoration on copies of the statues which the Ancient Greeks would have seen all around them. This archer is one of his most spectacular: an intricate design of blue, red, yellow and green diamonds interlock, to give the archer ornate leggings and sleeves. His quiver is decorated in a similar colour-palate, with a slightly different design, almost like scales. The bow is painted red and gold, and even the arrows are decorated red. The archer is one of the stand-out pieces in Brinkmann’s Gods in Colour exhibition, which has toured the world for the past 15 years.

In living colour

And Brinkmann is not alone in his attempts to reintroduce colour to ancient sculpture. The Museum of Classical Archaeology in Cambridge has also tried to bring some colour into its plaster reproductions of ancient statues. The original (now white) Peplos Kore – a statue of a young girl, wearing a long dress belted at the waist – stands in the Acropolis Museum in Athens. The dress of the Cambridge copy is painted bright red, with blue borders, and blue, green and white decorations. She has also acquired a pair of feet, lost from the original marble version, and a new left arm. The Acropolis Museum itself makes a bright option available too: they encourage visitors to their website to decorate their own versions of the peplos (dress), allow you to investigate archaic colours and see which colours were available to painters in the ancient world.

And the Greeks are not the only ones whose statues were painted: the Romans were similarly enthusiastic about brightening up their marble. Paolo Liverani, of the University of Florence, has worked on a project to recreate the statue of Augustus of Prima Porta. The emperor’s statue was discovered in 1863, and showed traces of the paint which once decorated it. A cast of the statue, its polychromy restored (and, in part, imagined), now stands in the Vatican Museum. The decoration has changed hugely since Greek times: the statue of Augustus dates from around 20 BCE. Augustus’s breastplate is decorated not with a geometric design, but with figures. His cloak is a deep red, the edges of his tunic are vivid red and blue.

And further south in Italy, we have one of the best-preserved sites from the ancient world. Herculaneum, near Pompeii in the Bay of Naples, was buried in ash when Vesuvius erupted in 79 CE. Its relics have been preserved differently from those in Pompeii, because the two sites are different distances from the volcano. Pompeii was hit with larger chunks of rock, for example, which destroyed the top floors of its buildings. Herculaneum still has carbonised wood in place, which was burned away in Pompeii.

In 2009, a team of scientists in Southampton began the digital recreation of a painted statue of a wounded Amazon warrior which had been found at Herculaneum. The front of the Amazon’s face had been destroyed, but her red hair, curling out from a centre parting (as Roman girls would have worn their own hair) was clearly visible.

The global audience for Brinkmann’s Gods in Colour exhibition has surely proved that there is an appetite for modern recreations of the brightness of ancient statuary. Aside from anything else, it reminds us how distant the Romans and the Greeks were from us, even though they often feel so familiar. The white marble statues or columns we have built in homage to the ancients say more about us – and the way we choose to imagine the ancient world – than they do about the people who lived 2,000 years ago or more. And perhaps the debate which had divided the art world for 100 years by the time Alma-Tadema was painting his version of the Parthenon can finally be set aside. Accustomed as we are to seeing the statues of ancient Greece and Rome in gleaming white, we understand them better if we remember their original colours.

Source: https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20180119-when-the-parthenon-had-dazzling-colours