Natasha Blatsiou | December 21st, 2017

A special multi-disciplinary team of experts at is opening a window for visitors onto the unknown, once-vibrant, colorful “life” of its ancient statues

Strolling among the statues of the Archaic Gallery at the Acropolis Museum, you can’t help but pause and admire how the hall’s bright light almost seems to penetrate the marble of the ancient carved figures and illuminate them from within. If you don’t stop to question this phenomenon, you might harbor the misconception that the statues’ white color is what gives them their grace and beauty.

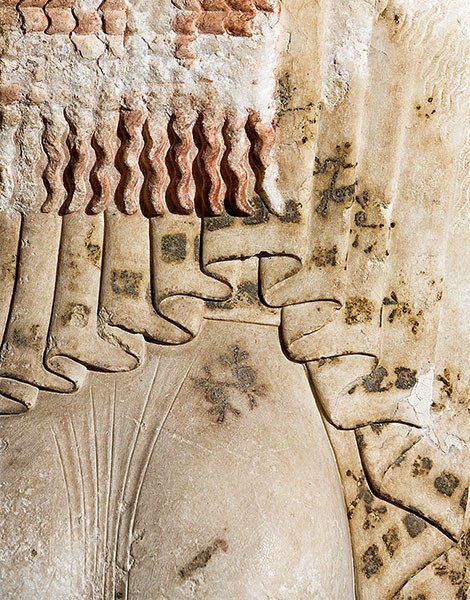

If one casts a sharper eye, however, remnants of color can be detected: red in the hair of the Peplos Kore, deep blue on the beards of the Three-bodied Daemon, green on the robe (chiton) of the Chios Kore and dark brown distinguishing the eyebrows and eyes of Kore 684. Here we have subtle clues to a former world rich in color and elaborate ornamentation, now preserved only as faint traces.

Since 2011, the Acropolis Museum has been studying and revealing its statues’ “lost” polychrome appearance. “We began the project having at our disposal an extraordinary body of material – the world’s richest collection of Archaic statues which have retained their colors. Subsequently, however, the results have proved even more exciting as we have come to the realization that the colors on the statuary was their sine qua non. Their polychromy is not a superficial decoration, but an essential element that adds to their aesthetic quality. It is an integral part of their identity,” contends the museum’s director, archaeologist Professor Dimitrios Pandermalis.

ON THE TRAIL OF LOST COLORS

It was the winter of 1885 when archaeologists unearthed this unique assembly of Archaic figures. Buried on the Acropolis in 480 BC, following the Persians’ disastrous attack on Athens, they have since been spared 2,500 years of further vandalism and wars. When archaeologists finally brought them back to light, they were surprised – not only because they had discovered such important works of Archaic sculpture, but also due to the excellent preservation of their original surface paint.

The damage suffered by the statues was relatively small, thus providing archaeological researchers with a promising corpus of evidence from which to draw definitive conclusions on the amazingly polychromatic world of ancient Greece. The watercolor representations of Swiss painter Émile Gilliéron, produced immediately after their discovery, and the detailed early analyses of Wilhelm Lermann (1907), have proved invaluable. Unfortunately, the field of conservation and techniques employed then for recreating ancient paints were not so advanced as to allow the statues’ colors to be reproduced with any precision.

The polychromy of the sculptures is not a superficial decoration, but an essential element that adds to their aesthetic quality.

Today, a century later, the investigation of ancient paint has made huge strides, thanks to new, state-of-the-art techniques now available to scientists. In the Archaic Gallery, it is not unusual to meet the Acropolis Museum’s team of laboratory specialists – chemists, conservators and archaeologists – as they endeavor to save the precious information preserved on the sculptures. Their only enemy is time, since each passing day is a further detriment to the millennia-old paints and surfaces.

“It all begins with observation – a process not at all simple, since investigators often observe and record what they are already familiar with, or have to synthesize knowledge from various sources to discover something new. The cultivation and continual refinement of one’s ‘ability to see’ is the first and foremost step in detecting colors,” notes Prof. Pandermalis.

This daily practice by the specialists, combined with a series of particular, non-destructive techniques, including spectroscopic analyses, leads to a determination of the statues’ true colors. Specialized photographic-imaging techniques reveal further details, such as the presence of Egyptian blue paint. In addition, efforts to reproduce ancient colors and actually apply them to samples of Parian marble have also shed light on the original techniques of ancient painters. “The aim of all these activities,” Prof. Pandermalis explains, “is to compose a database that will aid us in understanding why the original artist made the choices he did.”

A WINDOW ON ANCIENT GREEK CULTURE

So far, scientific research has led to several important conclusions. White, red, black and ochre (pale yellow to brown/red) were the ancients’ four primary colors, which Pythagorean philosophers believed were connected with cosmology and the four primary elements of the cosmos: air, water, fire and earth. For the ancient Greeks, colors constituted a means of classification: the gods had blond hair that radiated their power; warriors and athletes had brownish skin as a sign of virtue and valor; while women (kores) had white skin that signified the grace and glow of youth.

Historical sources tell us that in classical antiquity a sculpture finished without colorful paint would for its creator be unthinkable. The famous sculptor Phidias employed a personal painter for all his works, while Praxiteles was said to have had more appreciation for those of his works that had been painted by the eminent artist Nicias.

For the average viewer, however, an unpainted statue would have been something he could not comprehend, and would likely find unattractive. This becomes clear in the tragic play Helen by Euripides*. (Source: Transformations, Classical Sculpture in Colour, NY CARLSBERG GLYPTOTEK):

*My life and fortunes are a monstrosity, partly because of Hera, partly because of my beauty. If only I could shed my beauty and assume an uglier aspect, the way you would wipe color off a statue…

– Euripides, Helen, 260-263. (Translated by R.Kannicht, Heidelberg 1969)

In the gallery of “white” statues, the museum director points to several original works that appear side by side with digital representations of their true colors. “Ancient Greek sculptures today can resemble cemetery statues,” Prof. Pandermalis comments, “but when their creators crafted them, they wished to give them real life, to make them appear lifelike. Daedalus’ contemporaries used to say that his statues looked as if they could move. Unfortunately, today, the traditional perception of Greek statues as white still prevails from the 19th century, when viewers of ancient Greek art preferred to see these figures not as real people, but as idealized representations.”

“Is there no interest anymore, then, in such white statuary? No, of course there still is. Their misconceived whiteness is a fact that has emerged from the historical circumstances through which these sculptures have come down to us. The best way to overcome this phenomenon of history is to display digital representations that do not affect the original works, do not impact the original material, but lead to a significant moment of revelation in the viewing experience of our visitors.”

Through this journey into the sculptures’ past and digitally colorful present, one cannot but pause and consider a newfound emotion: the aesthetic pleasure of the statues’ intense original colors that brings to mind ancient sounds and smells and renders these pale figures full of animated expression. “Investigating the original paints, we gain something unique: the ‘look’ of the statues – that is to say, the expression of their soul,” remarks Prof. Pandermalis, revealing his personal passion for the high art of ancient Greek sculptors… and painters.

ANCIENT COLORS AND DECORATION

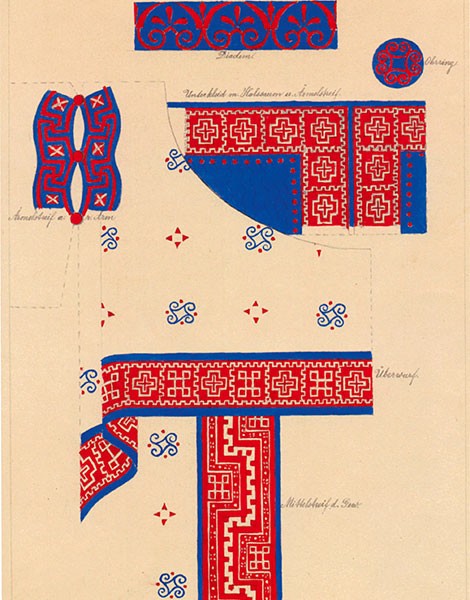

Primary colors commonly used on sculptures of the Archaic period included red in various shades, dark blue or light blue, black, yellow and green. The paint was applied in layers of various thicknesses. Among these colors, red was predominant, perhaps due to its easy accessibility and the symbolic value given to it by Mediterranean people. Blue or black was associated with marine life and Poseidon. On Archaic kore (maiden) sculptures from the Acropolis, green and brown have been detected in association with features of the face and head such as eyes and hair.

For the skin of kore figures, ancient painters used light-brown/yellow (ochre). The traces of color found in their eyes show they had a piercing gaze. The iris was decorated with two superimposed layers of red and brown paint that gave depth to their gaze and expressiveness to their faces. The pupil was black/dark. The eyelids were accentuated with black or dark brown border lines. On the hair of most kore figures, traces of brilliant red color are preserved, while occasionally a second, deep- brown layer is also evident, as in the Chios Kore. Light blonde or blue colors have also been observed.

The robes of kore sculptures are believed to represent actual clothing decorated with patterns, familiar to us from the painted decoration of vases. This was luxurious attire, indicative not only of female vanity, but especially of their social status and perhaps their votive character. The chiton, himation and peplos were adorned with bands of meanders, continuous spirals, palmettes, coiling tendrils, lotus blossoms and even pictorial scenes. Various accessories and types of head ornaments and jewelry – earrings, necklaces, bracelets and pins – as well as buttons and belts complete the kores’ ornamentation.